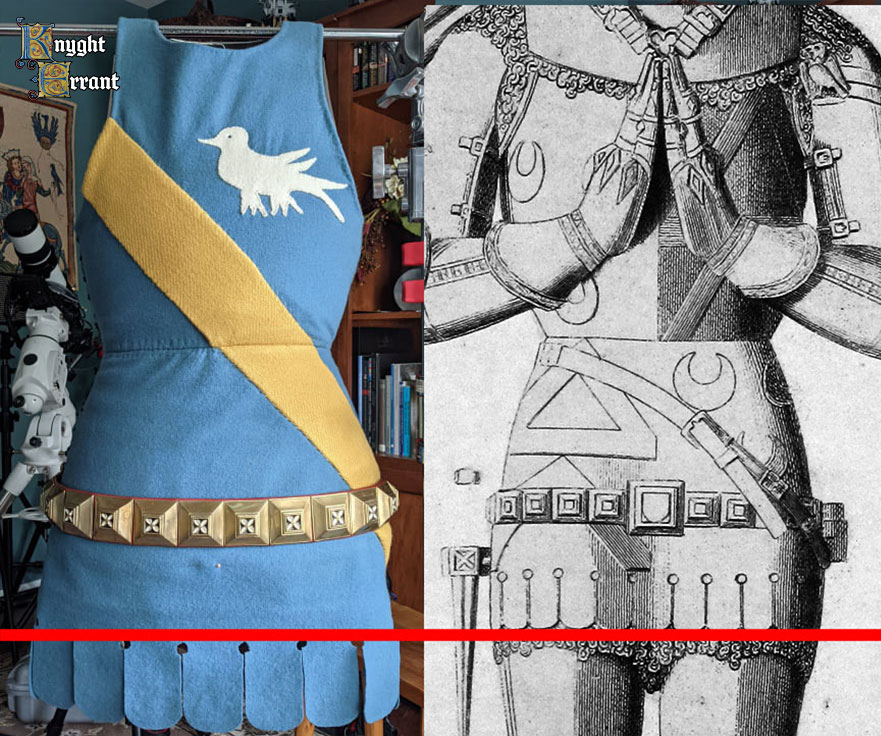

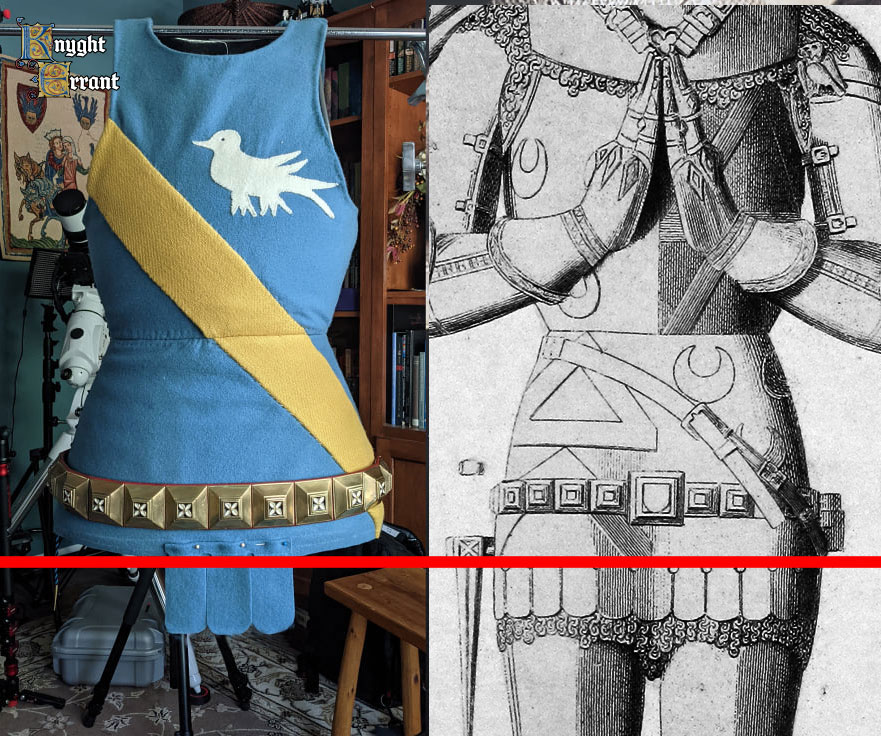

New projects have a tendency to bring hidden issues to light as they often produce a cascading effect on other pieces of kit that force us to address underlying problems. Of course we have the option to ignore those problems and claim ‘good enough’ but we can often do better. I’ve been working on building a jupon, which is in the case of early 15th century England, a tight fitting, sleeveless coat worn over the armor, often used for heraldic display. I’ve documented a lot of the build on my Facebook page, but I may cover the complete project in a video down the line. In building it, it forced me to confront some other things and take an honest inventory of how the intended visual look of my kit compares to the sources that I am using as primary inspiration. There’s always a temptation at this point to simply look for other sources that excuse a mistake, but if our goal is to do the best we can, we should be honest about our original intent and ask ourselves if we will truly be happy with leaving things we know we did wrong unaddressed.

To this point I had completed most of the jupon and was entering in to the final stages of finishing, but something was not sitting right with me. The overall proportions looked strange to my eye. There was too much skirt length compared to the bodice of the garment. I kept noticing that my jupon looked abnormally long compared to the sources. The upper edge of the dagging (the decorative shapes sometimes cut into the edges of a garment) on my jupon began well below where the bottom edge of the dagging is most commonly shown on high-relief effigies. So why not just shorten the garment? Well, the problem is that on virtually every single English effigy that is wearing a jupon within the timeframe I’m interested in, mail can invariably be seen in the small gaps between the dagging. This means that the lowest lame of the paunce of plates (the skirt consisting of hooped steel lames that protects the abdomen) cannot be any lower than the top of the dagging. If I shorten my jupon at all, you will immediately see the steel lames underneath. There is also another constraint on the length of the jupon; the underlying mail skirt. The mail skirt on our visual sources usually peaks out from below the bottom edge of the dagging so that it is clearly visible. It must also cover the tops of the cuisses, but just barely. This will constrain the length of the mail skirt, but it in turn constrains the length of the dagging on the jupon. If I simply left my jupon long, it would force the mail skirt to be excessively long in order to be seen. We can now see how these problems can quickly cause unintended second and third order effects.

I was coming to the realization that I not only had to make a serious modification to a mostly finished garment, but I was also going to have to make a serious modification to the underlying armor. The former is a time investment, but it is something well within my ability to fix. The latter would be beyond my skill to reverse once I decide to go through with it (it is absolutely reversible, just not by me, it would likely involve re-leathering the entire paunce of plates to do right). I had to think this through before I dug a hole I couldn’t get back out of. Once I cut those leathers… I had long suspected that I probably went a little too tall on the paunce of plates. With the historically earlier underlapping design of the lames, it felt a little too restrictive when raising my legs (i.e, in hip flexion). Things like sitting down, kneeling, or having to get up from the ground in full armor were more difficult than they should be or prevented me from achieving certain positions entirely. A certain degree of restriction comes with the territory, so we shouldn’t be quick to assume that restriction is equivalent to a problem, but there is a such thing as excessive restriction. Building my jupon forced me to accept that what I had suspected all along likely fell into this category.

When I originally had the paunce of plates built I insisted it be this long. In fact, after it was first built, we went back and lengthened it at my request! How could I not see that it was going to be too long at that point? I commissioned this armor well before the idea of building a jupon had even entered my mind so I was focused on the proportions of the armor being as it would be worn uncovered. One of the problems is that the sources I was looking at were almost all wearing jupons. This meant that I was trying to emulate the proportions of a covered armor (where the skirts allow a bit of mail to show beneath, but not too much) as an uncovered armor. This prompted me to make my lowest lame terminate where on the effigies it was really the bottom of the jupon’s dags terminating. The overall proportion matches, but I was not paying enough attention to what the jupons on the effigies were really telling us about the length of the underlying armor. There are certainly examples of uncovered faulds pre 1420 in England that are longer than mine, and after 1420 English plate skirts would become very long, but there’s a catch. Most of these later and longer skirts are made up of lames that lap in the opposite direction of mine, that is the upper lames slip under rather than over the lower lames. This arrangement is what most people would consider the normal direction of lapping. The benefit of this arrangement is that it collapses with far more ease than the opposite arrangement. The direction of lapping on my skirt is far more springy and after a little bit of collapse resists further compression. My hypothesis is that while this direction of lapping may have been common in the early development of faulds, and likely sheds downward blows and falling projectiles with ease, it is likely restricted to overall shorter skirt lengths because of its imposed limitations on lower body range of motion.

Wikimedia Commons

I made the decision to cut 2 lames off the bottom of my paunce and shorten the jupon accordingly. This should alleviate the physical restrictions I was experiencing in armor, and would also bring the skirt of the jupon into a better proportion with respect to the sources. This meant I would also have to cut off the already completed dagging on the jupon. This ended up being a blessing in disguise. When comparing to the sources, the original dagging I made was definitely too fat and too tall, giving the impression of oversized dags. Replacing them would add a seam line around the bottom circumference of the skirt, but the overall look would be much improved. The dags on the real ones seem to be somewhat close to the width of a plaque on the arsegerdyll.

Speaking of arsegerdylls… my big fear was that in shrinking the paunce, my plaque belt, which had previously been expanded to fit the new armor tended to sit just around the third lowest lame of the paunce. Removing two lames meant that the third lowest lame was now the bottom! Crap… I was afraid that it would now be too big and be capable of falling off the bottom of the skirt. I had a special extension made for the belt to fit my armor, and now it wasn’t going to fit anymore. This gave me even more pause before actually removing the bottom two lames of my paunce. I decided that this would have been the wrong reason to not modify something I knew deep down had to be modified though, and went ahead with it. If it turned out the plaque belt was now too big, I would have to deal with it, dismantle the belt, remove a plaque and re-attach the hinge with new brass pins, hopefully without mangling it. I put this out of my head and went on with the modification to the skirt. Afterwards I set up the armor again, laced on the jupon, opened up the plaque belt, held my breath, and put it on. I was extremely relieved to find that it sat right where it should and could not fall off the bottom of the skirt. I tried to wrench it off and it still wouldn’t go. Crisis averted.

If you made it this far, I hope you found this useful! While this post is about a jupon, the approach of comparing our intended goals with the sources is universal and applies to almost any living history project. Sometimes what seems like a straightforward thing to make reveals a lot more than you expect. Sometimes the process can be iterative, going back and forth between the sources and trying to understand why things aren’t working and what it implies about the rest of our kits! Now I can hopefully focus on completing the jupon without too many more major surprises! Then on to the next project!

Leave a Reply