Time, place and status. These are usually the three general guiding parameters a person will use to narrow the scope of their living history impression to something historically consistent.

Zooming in on the time part of that, the collective wisdom is usually to advise the newcomer to select a specific historical decade as a good target for their impression. The idea being that narrowing the focus to a particular 10-year span limits the breadth of the appropriate material culture, the current fashions, the current events etc., to be both manageable from a research standpoint and also to be close enough in time that the results of the research when realized as a living history impression are historically cohesive. If we start to expand our scope too broadly in time, we risk starting to pull from points in history that are separated enough that individual elements from the extremes are no longer appropriate to be in the same kit. If you want to be extremely picky, in some specific cases even a difference of 10 years can matter significantly in what may or may not be appropriate (a fully developed great bascinet is entirely appropriate for 1415 but would be very questionable for 1405) but its a good starting point. A span of something like 50 years or a century as a ‘focus’ is a almost always a non-starter. That is not to say that people didn’t hold on to older fashions or that certain things stood the test of time more than others (this is a topic that requires its own specialized treatment), but it is to say that those things must be sourced and scrutinized individually to ensure that they are indeed appropriate, not to just lazily use that as a blanket excuse to justify our personal whims.

I think one of the often overlooked aspects of our parametric puzzle is the generational effect. Generations, a group of people born within a certain span of time (generally accepted to be about 20-30 years) that tend to share similar social and cultural experiences and ideals are one of the most powerful factors in how a person expresses the material culture available to them during a given time. We may observe fashion changes and aesthetics in terms of the decades in which they occur, but the changes in generational perspective that are happening behind the numbers are one of the likely driving forces behind those shifts in fashion and tastes.

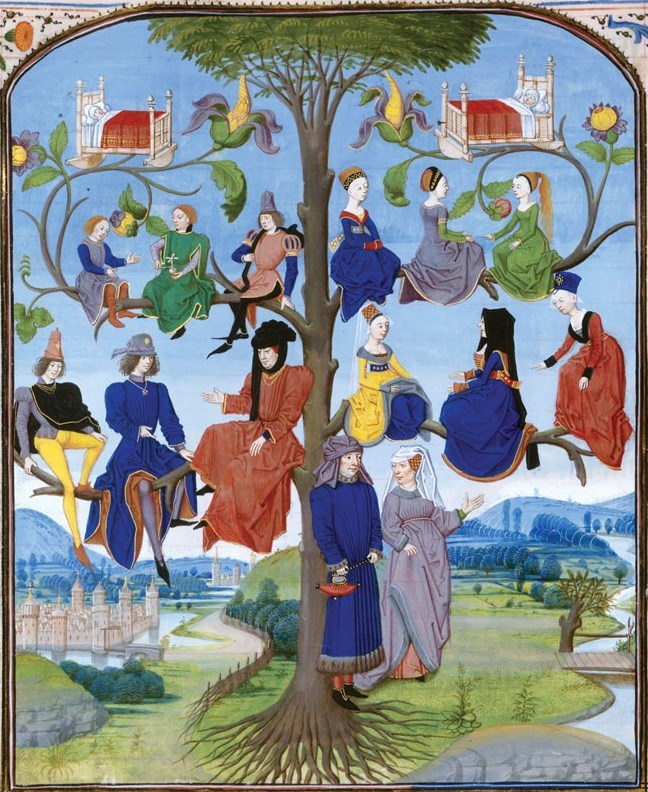

At any given time there may be three, four or even five generations of people alive depending on localized living conditions. Even though they may all live in the 1380s as an example, they may not all fit neatly into what we think of when we imagine the dominant characteristics of that decade. Certain things will of course be common to everyone in the 1380s, but there will be important differences between indviduals that are useful to represent through the medium of Living History. In the 1380s, you will have a generation of people born in the 1360s, who are now in their late teens and twenties, coming into adulthood. Using status and region as guiding factors, these are the people who are most likely to be on the bleeding edge of what we think of as ‘fashionable’ for the 1380s. This generation’s young men-at-arms might be the ones most likely to immediately adopt those new houndskull visors, or wear those extremely scandalous short doublets to court, suddenly finding themselves in need of codpieces on their hosen! Simultaneously, you will have an older generation of people who survived the Black Death of 1349 as children, and whose outlook on life will have inevitably been shaped by those events. As people approaching and in their mid-life, they are also going to be more likely to be the ones who, if appropriate, might still cling to some older styles of dress or equipment that were more fashionable in their youth (but not always!). This is further complicated by status. An older individual of significant wealth, may still prefer to be on the cutting edge of technology or fashion as a display of their wealth. It’s far more nuanced than simply thinking of ‘old = out of date vs young = height of fashion.’ It’s more that if incongruencies with what we think of as typical do occur, generational gaps are quite possibly a causal factor for those differences and should be considered when developing a believable living history impression.

I do want to make it clear that I’m not talking about the age of the reenactor themselves, but rather the age of the impression. Sometimes those things are aligned, sometimes we choose to reenact something that may be more typical of a younger person. How that is handled is up to the individual or group and is beyond the scope of what I’m talking about here.

Beyond thinking of generations simply as an additional parameter for developing a kit, it can also be a useful tool for analyzing broader trends in material culture during our research. When you look at changes in armor design or clothing fashion over time, sometimes you will notice certain things come in and out of fashion for a few decades for seemingly no reason at all. It’s possible that some trends are simply generational. Things that last 20 or 30 years are possibly trends tied to a specific generation. Things that last 40-60 years or thereabouts, may have gotten use for two generations before the next generation moved on to something else. Sometimes it just helps to think in those terms to make sense of the data when the impetus for change might not be so apparent or wasn’t driven by an obvious change in circumstance. I’ve also found that as an interpretational tool, it can help make some things more relatable to the public. Sometimes saying ‘this type of armor was in use for about 2 generations worth of soldiers’ is a little more relatable than the more abstract ‘this type of armor was in use for about 50 years.’ I think framing in terms of generations can be a useful tool for the living history enthusiast to keep in their back pocket for a variety of applications!

Leave a Reply