I think we could all agree that if you had never been exposed to mathematics in your life, you’d be setting yourself up for failure if you began your education by jumping straight into differential equations and Fourier analysis without first developing a broad foundation in basic arithmetic, algebra, geometry, calculus etc.. We generally accept that there are prerequisite skills that we need to develop before trying to tackle more complex and advanced problems. Could you do it? With enough motivation, raw intelligence, and a lot of time spent back-tracking, you might be able to work your way through a problem here and there and even arrive at a correct answer every so often, but your overall understanding of the material, your ability to perform consistently and to apply those skills broadly would be severely compromised. Yet we as a community of enthusiasts and hobbiests don’t think twice about trying to start with the more ‘advanced problems’ as we embark on our journey learning about arms, armor, and other aspects of historical material culture.

We see bits and pieces of hyper-specific information, isolated from its greater context scattered around the internet, and start to sweat the tiny details before we’ve tried to view the big picture and develop a foundation. We’ll jump straight into a high level discussion on Facebook about the minutiae of 1460s Italian export armor destined for the Iberian market, or, with no background instruction attempt to interpret mountains of manuscript illustrations from 1250 France (artwork is a deceptively tricky body of source material by the way. Being visual it can give the impression of being very accessible to a lay audience but it is a path fraught with peril where things that superficially seem to support a certain position may not be doing anything of the sort). Facebook groups and YouTube Channels (the irony is not lost on me) make this approach all too easy. You can end up in a situation where you know these very specific pieces of information but you can’t put them together or draw broader (or accurate) conclusions because of that missing foundation.

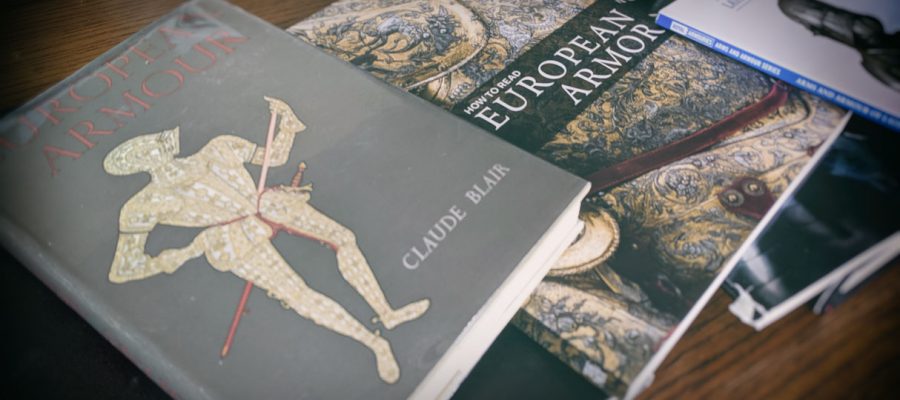

In many ways it’s seeing the results of those ‘advanced problems’ that sparks our interest in the first place. They are the things that tend to capture our imagination for the first time and trigger that sense of wonder that inspires us to dig deeper, which is great! We all need that point of entry, but sooner or later if we really want to understand, we need to take a step back and fill in that foundation. How do we do that? The overwhelming majority of us will never do this professionally, so it’s unrealistic to expect anyone to go enroll in a Medieval Studies program and take University level classes in Manuscript Studies and Art History just to become a reenactor or living historian. What we do have access to though, is a whole world outside of blog posts, videos, Facebook threads, and Wikipedia articles: good old fashion books. Those other resources are great to get you involved, for entertainment, and for the pursuit of very specific inquiries, but they are all essentially floating islands in a vast ocean of information and depending on the exact source, may or may not be accurate at all. We need a way to learn how to navigate the sea and observe the lay of the land to appreciate how those islands sit in relation to each other and whether or not that island is surrounded by hidden reefs waiting to shipwreck you. Volumes like Blair, Edge and Paddock, etc., are almost required reading before you start worrying about whether or not pairs of plates could be closed from the front as well as the back, or if that gauntlet design is a perfect match for a 1430s Kastenbrust harness. With a broad foundation, one can begin to understand research methodology; how the historical method works and essential skills like how to conduct source criticism. Without those skills, doing your own research can become rather frustrating and ineffective. You will always rely on others to provide information for you. Once you build that foundation, primary source material can become a little less daunting, you’ll be able to place things within a greater context, you’ll be able to answer a lot of questions for yourself and even if you don’t have the answer, you’ll know the right questions to ask (another oft overlooked skill). Being familiar with the source material also makes it a lot easier to find an answer. Knowing how and where to look is often a more valuable skill than trying to know all the answers at once (because you won’t). Then when you return to those online discussions, internet forums and the like, you’ll have a much greater appreciation for what’s being said, and likely a much more fruitful experience.

8 Comments

Leave your reply.